Prishtina: Modernism Delayed

by Eliza Hoxha and Ilir Gjinolli

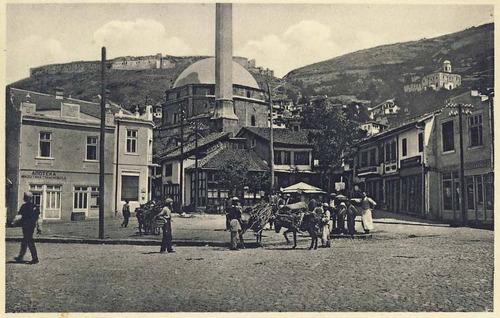

The processes of urbanization of the inherited ottoman city in Kosovo and the transformation of the society from agricultural to an industrial one started very late comparing to the other cities in the Balkans and Europe.

Between the 1914 and 1946, Kosovo remained within the territory of Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian Kingdom. Pretty much the same conditions were in the region in terms of influences of modern architecture and urbanism. This happened due to the lack of an architectural school and education. A limited impact from Austro-Hungarian and Italian architecture, mainly in public buildings and less in housing, can be traced from this period. This period is characterized with planed colonization of Kosovo during ‘20s and ‘30s as a discriminating policy of Serbian authorities, taking land from the local people and giving it Serbian migrants.

The process of colonization affected the towns and cities both in their physical and social and economic structure. Although the industrialization had been very slow, this process and transportation infrastructure affected outskirts of the cities putting edge lines and areas, which we can trace even today. Most of the built architecture from that period was for institutional buildings such as schools, government buildings, train stations and hospitals. The architects of these buildings were from different companies from former Kingdom of Yugoslavia, but also from other countries Hungary, Austria and France.

Clear cut with the tradition and traditional values happened in Kosovo after the Second World War, when Kosovo remained under the rule of the socialist Yugoslavia. The images of old curved roads surrounded with the outer walls and backyards which were creating blocks of irregular shapes, will disperse into pieces on the years to come under the construction of a new image for the cities followed by the slogan “destroy old and built new” which comes from the strophe of Internationale. Disappearance of traditional values and life styles through new forms of architecture after the World War II in most of Kosova cities, and in capital Prishtina in particular, started exactly by attacking their genius loci-the ottoman core of the city. It was a time when Kosovo had gone through a vast transformation including property transformation from the private to state and then to socially own. Destruction of the cultural heritage and the public space both in physical and in terms of use marks this period. Beside the buildings, the public spaces such as bazaars – ‘carshia’ and public gardens, disappeared in most of the cities. In Prishtina for example, which became the capital city of Kosovo in 1947, to legitimize the destruction while underlying public interest a new plan drafted ‘50 [1] besides many objections passed on the year 1953.

Bashkim Fehmiu, the only Albanian architect in Kosovo, being present in the public hearing of the Provincial Assemble of Kosova invited by Fadil Hoxha the President of the National Council of Province said that: “There were objections from many people about this plan. It was very unreasonable to destroy the old part having so much free area around it for the new city development. But at the end nobody took our concern into consideration” [2] The plan brought new ideas about the “re-model-ing” – “transformation” of the old centre to a modern one creating a space for two main building of power to come with e new Square of ‘Brotherhood and Unity’ in-between as a new crown and glory of a new city. The reconstruction project of Kosovo Assembly by a well known Yugoslav architect Juraj Neidhardt during ‘60s in Prishtina, is just a momentum marking modernism with universal character followed by first modernist housing project Ulpiana designed by Bashkim Fehmiu. The period between ’70s and late ‘80s, where seen as golden years for Kosovo. The Kosovo library designed by Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjakovi? is just an example to elaborate further architecture rooted in modern tradition but at the same time tied to cultural and/or geographical context blending Byzantine and Islamic architectural forms through many domes and squares. Other public buildings that marks this period are Printing House Rilindja designed by Georgi Konstantinovski, Radio and TV building, Youth and Sport Center designed by Živorad Jankovi?, Institute of Albanology by Miodrag Pe?i?. There are also Kosovo architects s been winners of BORBA award, the most prestigious architectural award in former Yugoslavia – Qemajl Beqiri for Primary School in Peja 1983, Lulezim Nixha for the Restaurant in Kosova B Power Plant -1984 and Sali Spahiu for Kosovafilm Studio-1987.

From above, the National Library in Prishtina (1983) by Andrija Mutnjakovi? looks like a motley cluster of cubes, varying in size and height, rather like a village. The domes supply even, natural light to the reading rooms. The cube shape contributes to the compactness and the sense of protection, which is further reinforced by the aluminum net of hexagons that is draped over the building.

Establishment of the school of architecture within University of Prishtina in 1978 was also a momentum to make possible the Kosovo community involvement in the taking decisions for future shaping of their built environment, because until then most of the projects and plans projects for Kosovo where made elsewhere in former Yugoslavia, mainly in Belgrade. Here we can refer to the first generation of Albanian architects starting from Bashkim Fehmiu and many others who graduated from Belgrade, Sarajevo and Skopje architectural schools. They took the initiative to start the architectural studies in Prishtina for the first time. It was a mix of teachers from Prishtina, Belgrade, Sarajevo and Skopje University. As soon as the first architects came out of the Prishtina School, young teaching staffs was coming up by extending their studies in the graduate programs in the former Yugoslavia. Although more architects were added to the architectural scene, many capital buildings in the cities throughout Kosovo remained unfinished, due to Yugoslav political and economical crisis in the beginning of ‘90s.

The new regime of Milloševi? detached Albanians from two main pillars of mental development of society: University and Media. The Albanians chosen a platform for surviving mentally/spiritually by organizing a parallel system of education in the private houses. These conditions brought to an ambiguous mental map of the cities for two different communities Albanians and Serbs. The centre of the city with regular public infrastructure became as a transit zone, since houses hosting schools and university where mainly in the peripheral housing areas of the cities. The city became a house for new Serbs, while a house became e city to Albanians. The pattern of the cities started to change drastically, due to changes in the housing typology, which developed mainly illegally and informally. Albanians were detached from everything what was public. During this time, religion appears again in the social and physical-scape, as it was seen as a platform for reclaiming a national identity.

Architects from all over ex Yugoslavia build also in Kosovo as in this case of Printing house by Macedonian architect Georgi Konstantinovski. | via forumshqiptar

Post war in Kosovo brought all post conditions with it, post communism, post industrialism, postmodernism and what not. After ’45, in the FSRY, the private turned into public and the destruction and development were done by the “state”. Today, it is the people-individuals who are doing both, demolishing and developing at the same time in a space where public is erasing and everything is privatizing more or less. At the same time this period is characterized with the raise of importance of public sphere and public space in particular. Both the governments and nongovernmental bodies have been putting the issue of public space in the highest positions of their political/non-political agendas. Public space and public services are considered as a useful polygon to orchestrate the power of government in demonstrating the commitment to investment for public good.

The architects who graduated in Prishtina gradually took the role of city sharpers in Kosovo. Some of them trying to lay the paths for a contemporary architectural practice, some of them just improvising design process and getting more to “turbo-folk” architecture. Encroachment of the professional codes of practice and standards in many projects developed in Kosovo by the inexperienced architects created an ambiguous architectural milieu. The result of this is a very small number of buildings designed in Kosovo after the last war that we could be proud of.

Being an independent state and having also a need on regulating the legal status, for architectural professionals in Kosovo, it is a momentum to rethink, reshape, regain or recreate a new mentality toward architecture and city making processes in Kosovo. Architecture is more a way of life and a cultural representation of our selves, therefore a debate and other forms of its representation of Kosovo should be open and present. The presence of Kosovo in Venice Biennial of Architecture in the last two exhibitions is just one of the ideas that can mark this new window.

CITE:

[1] General urban plan for Prishtina was drafted in Belgrade by Dragoljub Partoni? and approved after three years in the Provincial Assembly of Kosova.

[2] B.F. finished his studies of Architecture in Belgrade – interview done by author , July 2005, Prishtina Note: “Author was not allowed to write or tape the conversation with Bashkim Fehmiu so the quotations are not fix but more a comment based on the general discussion that author remembered”

This article was republished with permission from architectuul.com.